The cave-temple complex

The Early Christian rock-carved complex is located on the northern edge of Vankasar Mountain, about 3.3 km from Tigranakert. This complex comprises a church carved into the right vertical rocky bank of the Khachenaget River, a narthex, and a graveyard. The graveyard is accessible via a rock-carved road with walls adorned with numerous cross compositions and several Greek and Armenian inscriptions (Figs. 1, 2).

In 2006, the archaeological expedition of Artsakh completely cleaned and excavated the complex. Additionally, they discovered (Fig. 3) and partially excavated a rock-cut canal running parallel to the river at the foot of the rock (see the section “Canal”).

The rock-carved road leading to the church structures spans about 120 meters. It consists of six open-air halls (dimensions: about 9×6 meters), three narrow paths running along the edge of the rock, steps connecting the halls and paths, and an observation deck serving as an entrance.

Outdoor halls have one or two rocky walls (Fig. 4). Round holes in their floors and walls suggest that the halls had wooden roofs supported by logs. Generally, cross-compositions are positioned in the eastern part of the halls. It can be assumed that these halls served as unique prayer halls-dwellings, or waiting rooms for pilgrims before reaching the actual church structures. The size of some pits suggests that they may have had an economic function as well.

The stairs are adapted to the terrain as much as possible (Fig. 5). In their wide sections, two or three people can walk side by side; narrow sections can be crossed alone. Sometimes the steps are 0.6–0.8 meters high and can only be reached by climbing. In three places, the road passes through a narrow path carved into the vertical rock. To ensure a safe passage, special horizontal grooves were carved into the rock, which served as a handrail (Fig. 6). Only one person can cross these paths by holding onto the handrail. Approximately in the middle of the road, there is a cube-shaped entrance-observation deck (Fig. 7) carved into the rock. The structure features a wooden door frame with the rectangular entrance frame, the hole for the door hinge in the stone and clearly visible holes for dropping the latches. With the door closed, further passage along the road becomes impossible. The narrow and high steps, the narrow one-person walkways carved into the vertical sections of the rock, and the guarded entrance-observation deck may indicate that the complex could be protected from unwanted visitors if necessary.

The core of the complex comprises of a rock-carved church, a narthex, and a graveyard.

The church is situated approximately 50.0 meters above the foot of the rock. Its plan and dimensional composition are of special interest (Figs. 8, 9). The prayer hall is oriented a north-south and features an irregular layout (length: 5.8 meters, width: 2.4 meters, maximum height: 2.10 meters), terminating in the south with a slightly rounded altar. Notably, a more regular altar is situated within the eastern wall of the prayer hall. This suggests the possibility of an older, probably non-Christian structure that was later turned into a Christian one. The builders used the existing former dimension, but carved a new altar in the rock, oriented towards the east, for liturgical purposes. The significance of the eastern direction is further emphasized by the numerous crosses and cross compositions carved solely on the eastern wall (Fig. 10).

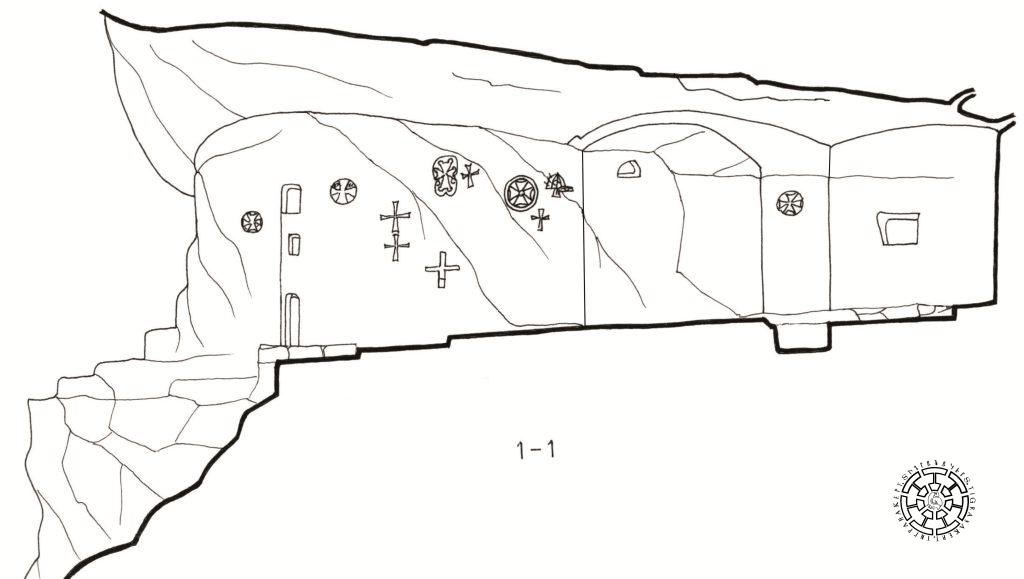

The northwest corner of the church is connected to the narthex, which is a west-east platform (10.8 meters long and an average width of 2.9 meters) enclosed on the west side by a 3.0-meter-high smooth-polished rock mass (Fig. 11). The natural gap between the entrance of the church and the narthex, judging by the traces on the site, was once covered by scaffolding, through which the church and the narthex are linked. In the southwest part of the hall, there are three rock platforms of different heights. The walls are adorned with carved large cross compositions-encircled crosses-placed on steps and high columns and decorated with floral additions and ribbons. On the floor of the hall, pits with circular and rectangular layouts, up to 20 cm deep, are dug into the rock, from which streams extend along the entire length of the platform. It can be assumed that these are technical features related to some pre-Christian ritual (pouring out, sacrifice, etc.) that took place here. Pits measuring 7 cm deep and 11–24 cm in diameter are made in the floor along the length of the canyon edge of the hall, at different distances from each other (25-45 cm). These prove that once there were wooden pillars supporting the railing. On the floor of the hall, on the surface of the rock, in front of the platforms, an image of three interlinked rectangles, with lines connecting the midpoints of their sides and vertices, is carved. A similar image is carved on the floors of the large church of Tigranakert and the church of Gyavurkala. They are the “boards” of the game popular in the East, today called “crosses and circles,” carved later when the churches were destroyed and their paved floors served as meeting places for nomads. The floor is quite sleek, which speaks to the large number of people gathered here as well as the continuous and long-term use of the area. On the eastern side of the hall, in the southern wall, at a height of 1.7 meters, a niche is carved (width 0.8 meters, depth 0.5 meters). Like the one on the altar of the church, this niche probably served to store various items. The graveyard extends to the west from the narthex (Fig. 12). It is a 13.0 m long open-air rock-carved hall with five rock-cut sarcophagi and a courtyard opening up to 5.0 m wide in front of them. At the time of excavation, the sarcophagi were already open, without lids, and did not contain any material or bones. Four of the sarcophagi measure 2.0×0.45 meters. All sarcophagi have 10-15 cm wide sides on which the lids were once placed. The depth of the stone coffins is 0.3-0.4 meters.

They are carved into niches in the rock bordering from the south, where, as well as on the surface of the rock, cross compositions are carved. The graveyard ends with a stage (Fig. 13), where on the east wall is a 20-cm-high, two-stepped base bearing a broad-winged cross raised on a pillar with schematic bird carvings attached. On both sides of the upper wing of the cross, the Greek inscription “IC XC” (Jesus Christ) is written. Three 0.6-meter-long rock steps lead up to this sculpture. A wide platform adjacent to the stage from the south may have served to place the ashes of the deceased. It can be concluded that the funeral liturgy took place here. Along the entire length of the rock-carved road, from the foot to the rock-carved church, crosses and cross compositions adorn the roadside rock wall (Fig. 14). They are particularly abundant in the hall, church, and rock-carved graveyard. While some crosses are simple and carved by unskilled hands, the majority are intricate cross compositions requiring precise measurements and pre-made sketches to ensure the symmetry and clarity of details.

These elaborate cross compositions exhibit stylistic similarity, emphasizing essential dimensional, constructive, and ideological dominants, and were created during the complex’s construction. A significant part of them, including the eastern altar of the church, was colored red. In the compositions created at the time of the original structure, the crosses are generally equal-armed (there are also some crosses of stretched proportions), sharply widening towards the edges; they are included within multi-profile, rope-weaved, and triangle-ornamented circles, set on high columns or poles. Generally, plant-floral, ribbon, and bird motifs are incorporated within these compositions. If the equal-armed cross within the circle symbolizes the theme of light (and triumphal), the vegetative and bird ornamentations, along with the ribbons, allude to the theme of the tree-of-life and the adoration of the cross. These early cross compositions bear striking resemblance to Armenian early Christian cross compositions dating back to the 5th-6th centuries. They share compositional similarities with the cross compositions found at Yereruyk, Tsiranovor of Parpi, and especially Tsitsernavank. It is noteworthy that the encircled crosses display broader parallels, up to the Irish high crosses. Chronologically, the next group of crosses dates to the 9th-10th centuries. These are linear crosses of elongated proportions with a pair of attachments on the edges of the wings. There are a certain number of irregular crosses carved by pilgrims themselves, the dates of which remain uncertain.

Three crosses in the church and graveyard bear Greek inscriptions of Christ-Christograms. If we keep in mind that Tigranakert was founded as a multi-ethnic city, including the population brought by Tigranes from Asia Minor, the presence of Greek inscriptions can be explained by the presence of the Greek community in the city.

Three Armenian inscriptions are carved next to a cross-carving on the eastern wall of the church. They are personal names, added later by pilgrims. Among them, the personal names “Didoy” and “Hama[m]” can be distinguished. It is likely that in the person of Hamam we are dealing with a famous prince of the 9th century, whose name is also mentioned in the inscription on the lid of the Gyavurkala sarcophagus.

The cave complex originally represented a series of natural karstic caves. In the ancient period, its upper cave part (where the church and the narthex are now) was turned into a tomb-worship complex. In the 5th-6th centuries, the ancient complex was transformed into a church and a narthex through dimensional changes. The graveyard was added, sarcophagi burials were carried out, the road was built with its defensive components, and the main part of the cross compositions, including those with Greek inscriptions, were added. At some point in the 7th-8th centuries, it became the seat of the Arab garrison, and it is likely that the narthex painting was added at this time. In the 9th-10th centuries, pilgrims added new but mostly primitive crosses and inscriptions in Armenian. After that, the complex was abandoned. At the end of the 20th century, when the residents of the neighboring Azerbaijani village tried to scratch the cross-sculptures, hundreds of scribbles with their names appeared on the walls of the complex, which significantly damaged the old sculptures and inscriptions.