The Antique Quarters

The main urban quarters of Tigranakert in Artsakh occupied the lowland areas at the foot of Mount Vankasar, extending from the northeast to the southwest.

Research on these quarters of was conducted during two periods: 2012-2015 and 2019-2020, in the southern part of the urban area, by the excavations of the sites located 114 meters apart. The sites are tentatively named Antique First Quarter and Antique Second Quarter (Fig. 1).

Regarding the Antique First Quarter, excavations began in 2010 after the accidental discovery of a medieval stone-cist tomb. This discovery revealed evidence of burial practices within an antique cultural stratum. Subsequent excavation efforts, covering an area of 700 square meters, were concentrated west of the tomb. As a result, at a depth of 1.25 meters, a spacious dwelling-economic complex was opened, displaying three structural and chronological periods with a regular pattern of successive archaeological layers.

The upper, early medieval cultural layer (second half of the 4th century AD-7th century AD) is represented by separate stone-earthen structures, which do not form an image of complete rooms. They are accompanied by tonirs (oven in the form of a deep round hole in the ground, the walls of which are lined with clay) and pottery. The foundations of the lines were laid on the walls of the middle layer, Late Antique (second half of the 2nd century AD-first half of the 4th century AD), or on the mortar of raw bricks covering them. In turn, the Late Antique walls, were built upon the walls of the lower, Late Hellenistic (early 1st century BC–first half of the 2nd century AD) rooms in the quarter (Fig. 2).

Within this layer, a north-south axial wall measuring 25.50 meters in length and 0.90-1.10 meters in width was discovered. On both sides of this wall, the scattered areas were built with quite large groups of rectangular buildings, forming a dwelling-economic large complex (Fig. 3). This thirteen-room complex has a simple and rational floor plan. It was used in late antiquity, also undergoing some reconstructions. These reconstructions included redistributing the spaces of the large rooms, to create new smaller ones, thereby altering their functional significance.

The selection of the area for the Second Antique Quarter was based on the presence of observable traces in the cut of the stream passing through here. In 2018-2020, this area was thoroughly explored, with a 300-square-meter section (Fig. 4) excavated. The main structures were uncovered at a depth of 1.50-1.65 meters. The stratigraphic picture here is closely resembles that of the First Quarter.

In the upper layer, small and medium-sized cracked stone and earthen-mortar structures were revealed. These structures outlined the corners of several rooms and sections of walls, accompanied by complete and fragmentary samples of their early medieval pottery.

In the middle layer, at a depth of 0.40-0.80 meters, the remains of 10 buildings were confirmed. According to the accompanying material culture data, refer to the late antique era (second half of the 2nd century AD-first half of the 4th century AD).

In the lower, third layer extending to the ground level, rooms with smoothed stone surfaces were exposed. These rooms featured vertically arranged wider walls and were placed throughout the excavation area on both sides of the central axis wall, stretching from east to west, forming a regular plan network (Figs. 5-7).

The complex research of the architectural, construction, and archaeological evidence confirmed by the excavations of the two quarters has revealed that they are the parts of the southern wing of the Hellenistic Tigranakert urban area that were built with a unified architectural concept. The construction was carried out with groups of large quadrangular buildings, which were placed in the sections formed by the intersection of the axial walls stretching from north to south and from east to west, creating dwelling-economic complexes. In Late Antiquity, while maintaining this basic floor plan, certain reconstructions were made, redistributing large rooms and creating new smaller ones. It appears to have been associated with urban population growth.

The data concerning the construction technique of the urban structures indicate that the stone foundations of the rooms and the lower rows of the walls, embedded into the clay foundation of the site were constructed using a combination of clay stone interlayer and stone double-faced techniques. The upper portions of the walls were built with raw brick. The rooms were connected by entrances featuring large, flat-faced stone sidewalls and tiled thresholds. In the rooms, sections of the walls were plastered with clay mortar, with traces of bleaching powder in some places. Additionally, the floors in the economic areas were found to be perfectly trodden and tiled. Squared slabs preserved at some distance from each other on the floors and fragments of basis suggest the existence of rooms with wooden columns and scaffolding ceilings. The central entrance opened on the western side of the First Quarter, formed by solid walls neatly lined with large stones, opening into a long corridor passage (length: 6.50 meters, width: 2.00 meters) that provided communication between the northern and southern wings of the complex (Fig. 8).

The materials uncovered during the excavations provide valuable insights into the lifestyle, occupations, and economic activities of the inhabitants of the settlements. In the rooms, the hearths arranged on the platforms slightly elevated above floor level, as well as tonirs embedded into the foundation, indicate the means of food preparation and heating within the apartments. The discovery of a fireplace built with raw bricks in one of the rooms of the Antique Second Quarter underscores the presence of a significant civilizational achievement. This reflects the influence of Hellenistic ecumenism in Tigranakert of Artsakh. The presence of limestone marble mortars, pestles, bedstones, and runners of the millstones placed next to them, pressing matters fixed to the paved surfaces of certain parts of almost all rooms, shows the intensity of agricultural product cultivation. The discovery of sherds of large-sized jars, pots, and tubs, huge millstones, and the analysis of archaeological plant remains, which were placed into the floors of economic rooms, represent the agricultural and viticultural economies. This economy is the basis for the development of the Hellenistic city. The presence of churns, strainers, and pots of various sizes indicates the high level of development of the cultivation of livestock products (Fig. 9).

The proofs of the developing crafts in the city are the iron weapons and tools representing metallurgy found in the rooms (hook daggers, knives, scissors, pointed tools), bronze arrows, body care products, and grooming products (awl, fibula, bracelets, rings, earrings, bronze mirrors, hairpins, etc., Fig. 10).

The various size heads of the spindle used for spinning threads of different fineness, weaving combs (known as ktutich in Armenian), and piles of cone-shaped, pyramid-shaped, and donut-shaped clay parcels of the weaver’s loom, which create carpets, rugs, and other types of textiles, are found in large quantities. These artifacts represent the significant role of this craft in the urban economy (Fig. 11).

Various bone items were found during the excavations: knife handles, two-bladed cutter-scrapers of different sizes, small buttons for fibulas, and buckles (Fig. 11). Stonemasonry is represented by the assortment created by three methods of stone processing:

a) stones with rough, flat, and edged surfaces, which were used for the creation of walls, columns, bases, and floor paving in the Hellenistic period.

b) small objects created by the artistic processing of stone: the bottom of a serpentine vessel; a fragment of the lip of a marble vessel; a limestone basis-small piece; a scepter stone head; fragments of stone bowls (Fig. 10).

c) stone tools, polishing tools, whetstones (Fig. 10); mortars; stones for millstone; door hinges; bomb stones; etc.

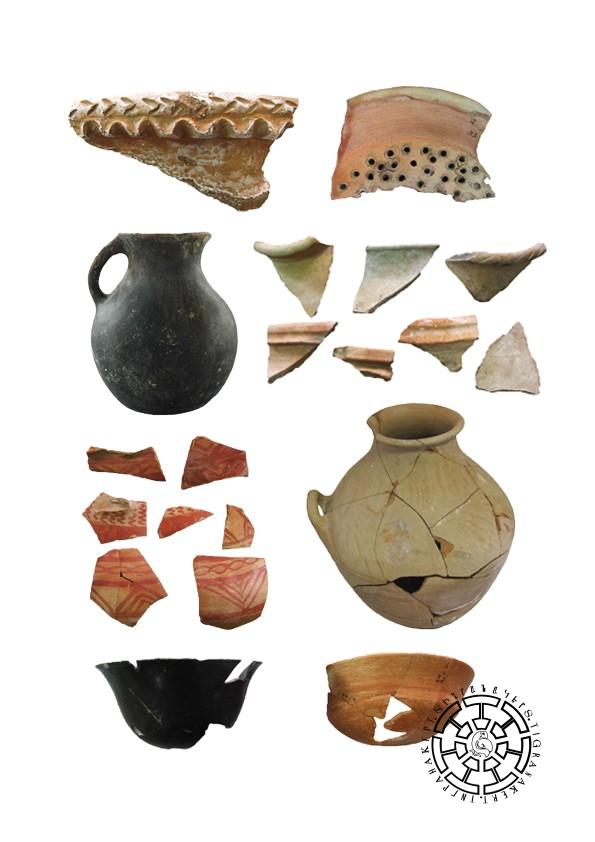

The discovered glass products, although not very abundant, are represented by brilliant examples of glass products from both periods. It is unique with a hemispherical body, the part of the cup with an inward lip. It was made in a mold from a glass mass of a light greenish hue, thick and finely polished (Fig. 12). Pottery, including dishes, kitchenware, and economic pottery, constitutes the absolute majority of the archaeological finds. The Hellenistic colored patterns, along with the splendor of the assortment and the abundance and exclusivity of the forms of the black-glazed selection, represent the peak of pottery development in the region (Fig. 9).

The objects of everyday life and worship imported from different countries, such as fragments of black-glazed lekythos, amphora with finger-shaped bodies, antique glazed vessels of unguentarium, terracotta figurines, and censers (Fig. 13), evidence that the residents living in the districts led an urban lifestyle. They were engaged not only in cultivating agricultural and livestock products and producing handicrafts but also in fostering lively commercial and cultural relations with Hellenistic urban centers both in their native regions and neighboring areas.

These explored parts of the southern quarter were converted into a cemetery in later centuries, leading to significant damage to the integrity of the buildings and cultural layers in this area. A multi-dimensional study of the anthropological data on these burials, conducted by the expedition’s paleoanthropologist Paul Bailey, found that the burials refer to the 12th-13th centuries. That is consistent with the data on the archaeological studies, as the layer from that era, characterized by specific structures and pottery, especially the availability of the medieval glaze range, was not verified in the Antique Quarters, which is definitely present in the Fortified and Central Quarters. It appears that life in this part of the settlement ceased in the 6th-7th centuries.