The Anthropomorphic Obelisks

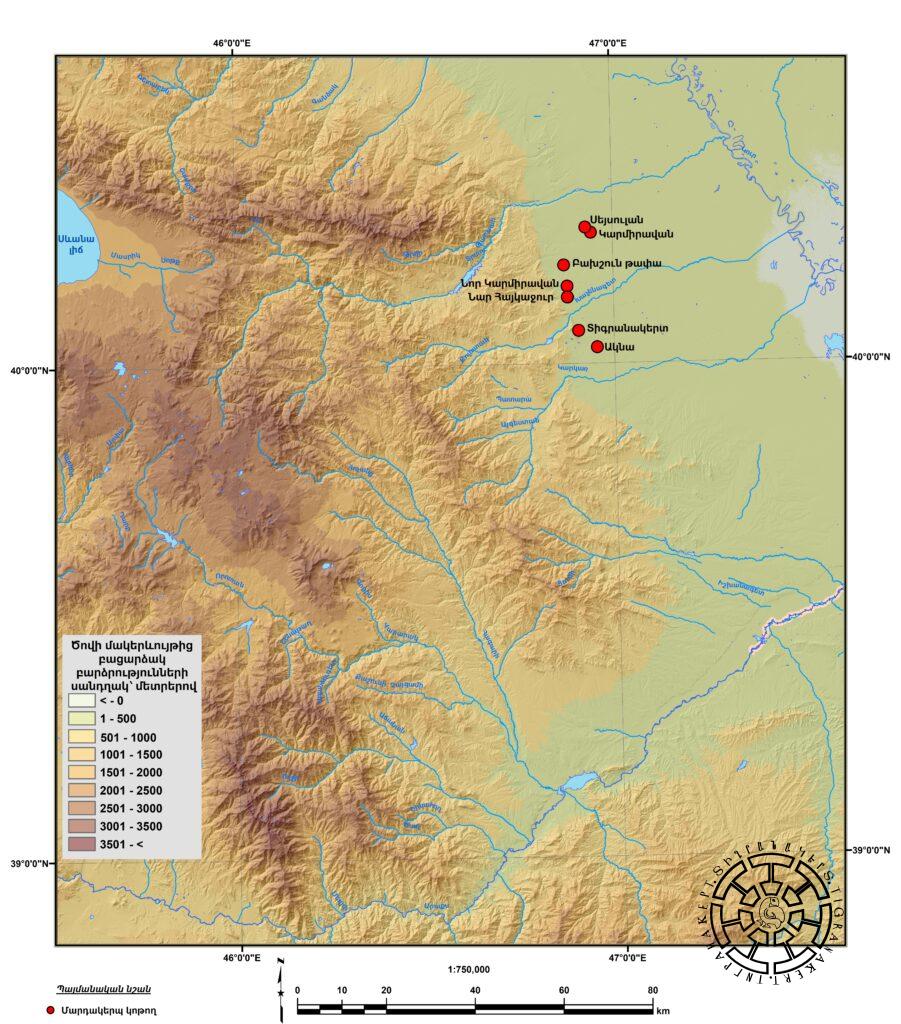

The anthropomorphic stone stelae were widespread in the longitudinal area merging the highlands and the steppe of Artsakh, stretching approximately 30-40 km. They are scattered especially in the north-eastern regions of the Republic of Artsakh, in and around Martakert, in Tigranakert, as well as near the Gyavurkala settlement, which is not far from the latter, and in the territory of Nor Karmiravan village. Several monuments from these places were transferred to the Artsakh State and Martakert Historical-Geological museums during the Soviet years, and some are still located in the open field (Fig. 1).

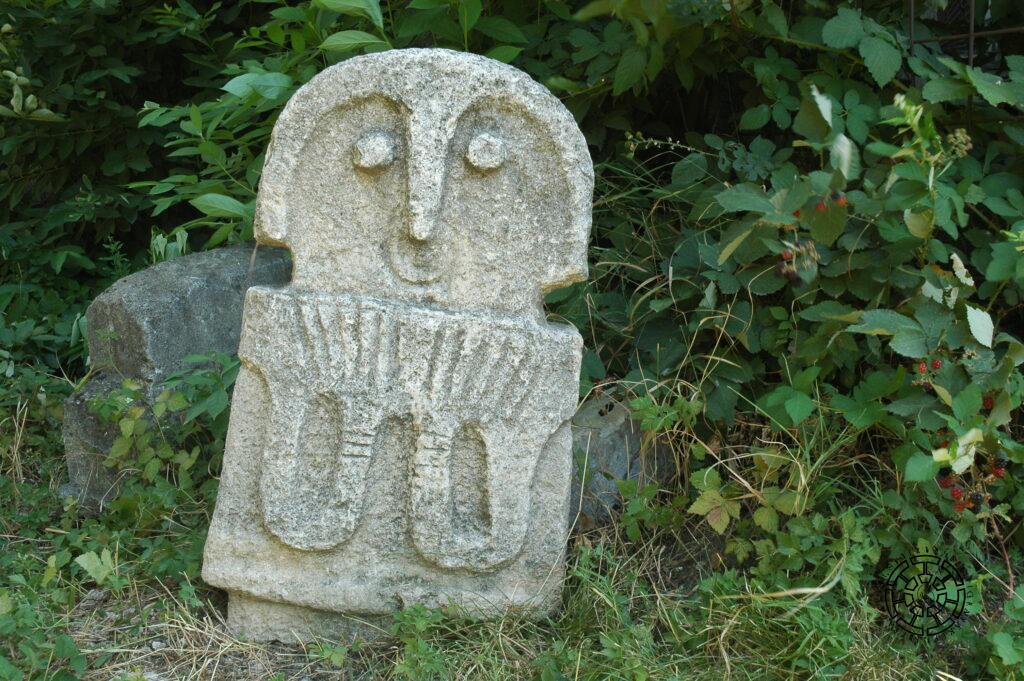

These stelae are rectangular, flat longitudinal slabs that are given an anthropomorphic appearance by sculptural processing. The main axis of these sculptures is the human body, and the remaining components are valued iconographically and semantically as a result of their connection to it (Fig. 2).

Although the first similar stelae have been known since the 1960s, there have not been many dedicated studies on them.

It is known that these areas were not sufficiently studied during the Soviet years for well-known reasons. And the existing research is obviously politicized. This also applies to the anthropomorphic stelae, which some Azerbaijani researchers have presented as Albanian, trying to see their prevalence, especially in Artsakh, as the presence of an Albanian ethno-cultural substrate. And only as a result of the liberation war in Artsakh was a new opportunity created for researching the ancient history and culture of the region.

More than 30 anthropomorphic stelae have been authenticated so far. It is not excluded that in a larger spatial area, physically inaccessible to us, in the eastern part of the Artsakh steppe and in the Mil steppe lying east of it, they were not limited to this.

Iconography

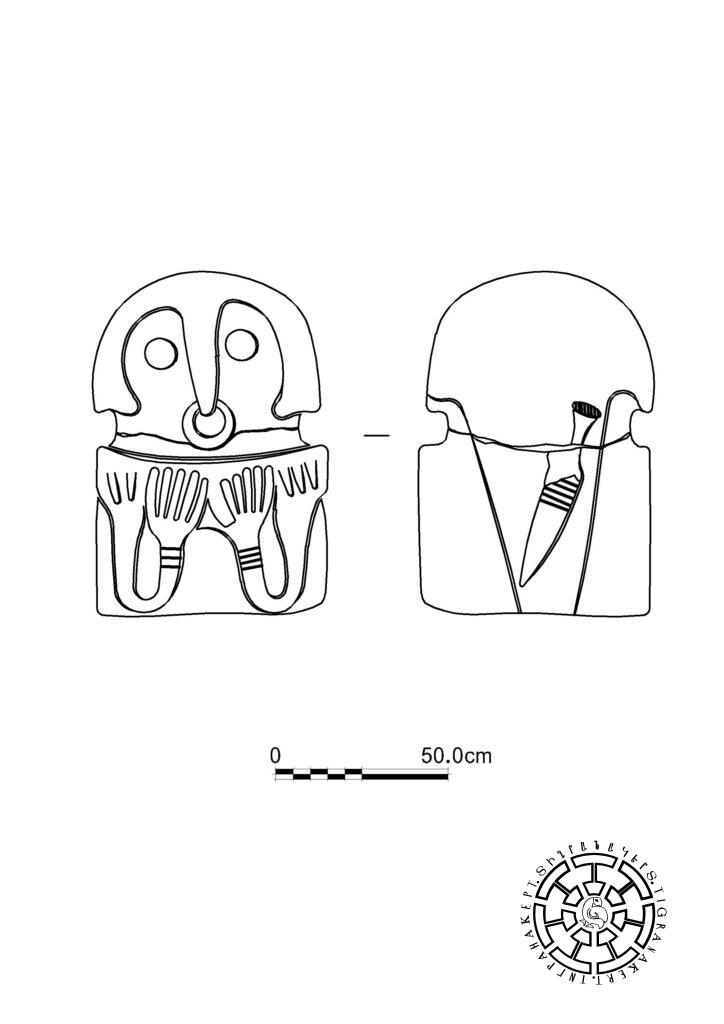

The longitudinal slabs of anthropomorphic stelae are divided into three parts by two wide horizontal groove-bands, “separating” the three parts of the body: the head, which occupies approximately a little less than a third of the volume of the entire stele, the torso, and the area below the waist. The part below the body, which was intended to be embedded in soil or a special foundation, was usually lightly polished. The monuments are approximately 30-60 cm wide, 120-140 cm high, sometimes up to 250 cm high, and 20-30 cm thick (Fig. 3). All the known stelae are made of limestone, extensive sediments of which and mines with traces of old cultivation are widespread in the eastern foothills of Artsakh.

The descriptive examination of the stelae allows us to confirm that the iconography presents us with at least two complexes: a. physique and b. outfit (including armor and decorations). Physically, one can distinguish hands, nose, and, as a rule, eyes. Among the outfits or other decorations depicted on the stelae are a headdress, a dagger, a bracelet, and a ring. The absence of hair, ears, mouth, and sometimes eyes, and the dagger depicted with a slant on the back at the waist, make more than likely the presence of other complexes of clothing and equipment, which were simply not seen and depicted as important (Fig. 4). This suggests that we are dealing with symbolic iconography; rather than depicting the actual appearance, these stelae represent signifier-meaningful components. We can conclude that the stelae depict men, mostly in protective outfits.

Topography

The topography of the stelae is not very diverse across various detection centers, which can be classified according to the following settlements:

a. Martakert (Bakhshun Tapa)

b. Seysulan

c. Karmiravan

d. Chankatagh

e. Gyavurkala and surroundings

f. Salahlu

g. Nor Karmiravan

h. Tigranakert.

These locations served as the primary sites for the creation and erection of these stelae. While the exact origins of some stelae remain unknown and most were not found in situ, it is clear that they were moved to their secondary place of usage from nearby areas.

Around the stelae, numerous large, rough, elongated stones are found. Some of these may have once been brought here for the purpose of creating stela.

Examining and combining the information on the discovery of stone anthropomorphic stelae in Artsakh, it can be observed that the monuments were found at elevations up to 500 meters above sea level. This area corresponds completely to the meadow-steppe zone of Artsakh, covering the southeastern part of the Lesser Caucasus, including the western part of the Kura-Araxes plain, the eastern part of the Artsakh steppe, and the extreme west of the Mil steppe lying east of it.

All the listed hearths are located in the inner valley of Khachenaget, where the river flows into the steppe or in its vicinity. These areas are highly fertile, suitable for both cattle breeding and agriculture.

Chronology and Function

The stone anthropomorphic stelae of Artsakh, by their function and semantics, represent a system that reflects ideas about death, ancestor worship, and the structure of the world in general. To understand the function and ideology of the stelae, it is very important to first establish their chronology.

As mentioned, most of the stelae were not found in their original locations. In this series, only the group of stelae found in Nor Karmiravan can be attributed to their initial environment. Here, the excavations of the Artsakh archaeological expedition verified the tomb surrounded by a cromlech and the stelae lying in its different areas (Fig. 5). The archaeological material found in the tomb, which includes approximately 40 vessels of different sizes and shapes, bronze and iron samples, and bone objects, allows us to date the burial and the anthropomorphic stelae associated with them to the 8th-5th centuries BC. The Artsakh stelae refer to an early group of stone anthropomorphic stelae covering a wide area. The comparative examination of such monuments also speaks in favor of such a dating of the stelae. It is likely that the appearance of these stelae in Artsakh was connected with the first penetration of the Cimmerians and Scythians into Anterior Asia, which happened in the 8th century BC.

Concerning the function of these stelae, it can be noted that the stelae found in Artsakh, as well as their known parallels, were most probably gravestones and/or cult symbols that were placed on a pedestal or without a pedestal on top of a burial mound or in the center of a sanctuary, and it is not excluded that they were also placed on in-ground burials. These stelae were erected in the event of the death of any member of the collective. Probably, the speech is about an individual from a high social class. The depiction of a commander-military leader and/or hero-warrior is the most probable for Artsakh stelae. Some stelae found in the territory of Artsakh were later reused mainly as building materials.