The coins

One of the important results of the archaeological research of Tigranakert is the coins, which date from the first century BC to the XX century. They are an important source both for dating the archaeological layers and finds, and for revealing a description of the city’s commodity economy and trade-cultural connections.

Coins of the Hellenistic Period

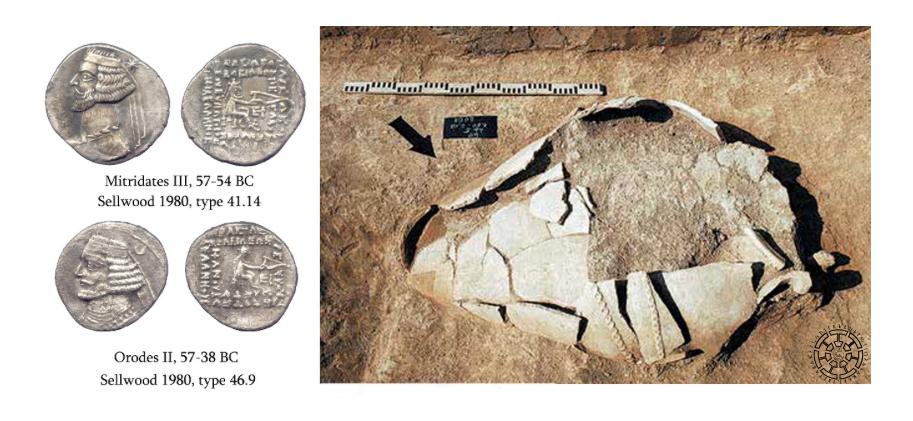

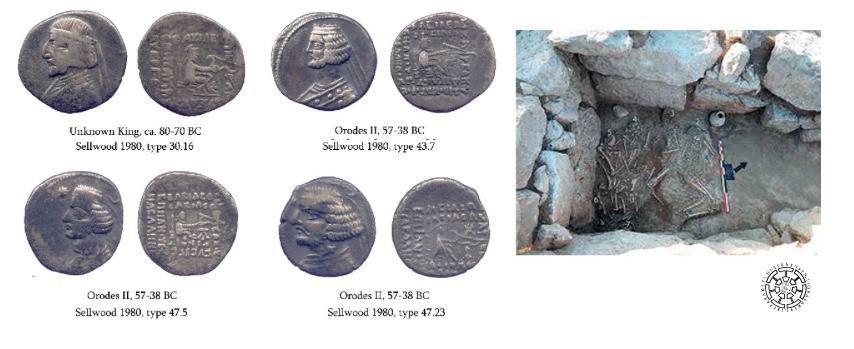

During the excavations, seven Hellenistic coins were found, all of them Parthian silver drachmas issued in the 1st century BC. The coins were discovered in tombs during excavations carried out in 2010, 2016, and 2017. In a late Hellenistic cemetery located one and a half kilometers northeast of the city, the expedition uncovered five pithos burials as well as an additional pot burial within the fortress’s territory. Three of the seven coins were found in two of the pots excavated in the grave fields, while the remaining four coins were unearthed in a stone burial box placed adjacent to the pots in the same grave field. Coin finds from antique burials play a significant role in clarifying the timing of Tigranakert’s establishment. The presence of the colored pottery authenticated in the burials and resembling the hundreds of examples found, particularly in the Fortified Quarter, clearly indicates the first half of the 1st century BC. This timeframe aligns perfectly with the political context of Tigranes II founding the cities bearing the same name in Artsakh and Utik, specifically during the years 80-70 BC.

One of the two coins in pot No. II was found in the mouth of the deceased, the other was located between the ribs (Fig. 1). Additionally, a glass bead covered with gold foil, a bronze mirror, and iron rings were found in the pot, along with a colorful jug resting on the bottom of the pot from the outside.

In the stone box tomb, four coins were found amidst a pile of bones from the four originally buried deceased, as well as under the skull of one of the two later interred individuals in the same tomb (Fig. 2). Among other findings in the tomb were a bronze crescent medallion, a well-preserved colored jug, and fragments of another colored jar.

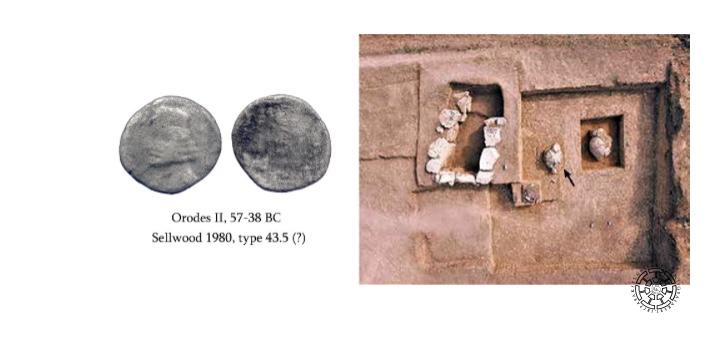

Due to the very poor preservation of the skeleton in pot No.V, the location of the coin is uncertain (Fig. 3). The pot also contained beads made of glass paste, fragments of bronze, and iron rings.

The earliest coins were issued by an unknown Parthian king (Sellwood, type 30) and date back to the 80s-70s BC (Fig. 4.1). One such coin was found in the same tomb as three drachmas of Orodes II (57-34 BC). According to data from the History Museum of Armenia’s (HMA) collection, Orodes II’s drachmas are present in the hoard of Sarnakunk, the princely mausoleum of Sisian, and one was found in Tsaghkadzor.

A drachma of Mithradates III (57-54 BC) was also found alongside a drachma of Orodes II in burial pot II (Fig. 4.2). In the HMA collection, three out of the 22 drachmas of Mihrdates III originate from the Sarnakunk hoard.

The remaining five drachmas found during the excavations are different issues of King Orodes II (Fig. 4.3-7). In the South Caucasus, the drachmas of two prominent Parthian kings, Mithradates II (123-88 BC) and especially Orodes II (57-38 BC), constitute the majority of coin finds from the II–I centuries. Following the death of Mithradates II, the Armenian king Tigranes II (95-55 BC) successfully vied with the Parthians for dominance in the region. His son, Artavazdes II (55-34 BC), was an ally of the Parthian king Orodes II, who defeated the Romans. The HMA collection contains 157 drachmas of Orodes II, 11 of which are from the Sarnakunk hoard, and 22 are from different parts of the Republic of Armenia.

Among the coins found in the tombs of Tigranakert, three are minted in Ecbatana, two in Ragae-Arsakia, and one coin each in Mihradatkert and Susa. The first six out of seven coins were issued in the mints closest to our region, which also produced the most abundant products. It is natural that coins issued in those cities prevail not only in the Tigranakert of Artsakh but also in the entire South Caucasus.

We can notice that in all three burials containing coins, the drachmas of Orodes II are present, which are chronologically the latest in the given tomb complex. This circumstance and the absence of coins of the king Phraates IV (37-2 BC) following Orodes II in the burials can be the basis for dating the above-mentioned burials from the late 50’s to the first half of the 30’s BC.

Coin hoards and stray coins found in the South Caucasus prove that from the last decades of the II century to the last third of the I century BC, in the monetary economies of Armenia, Iberia, and Caucasian Albania (Aghvank), Parthian drachmas prevailed in the monetary mass that arrived here from different countries. From the last decades of the I century BC, but more specifically starting from the I century AD, the coins of the Parthian kings in Armenia almost stopped playing any role, giving way to the gold, silver, and copper coins issued in various places of the Roman Empire, particularly in the eastern mints. And in Iberia and Aghvank, especially in the first one, along with the significant increase of Roman coins, starting from the second half of the I century AD and especially in the II century, the so-called Gotarzes-type Parthian drachmas, which are rare in Armenia, became widespread.

The presence of coins in the tombs of Tigranakert and the large number of them compared to the number of excavated tombs testify to a city with a developed monetary economy. For comparison, it is worth mentioning the 26-hectare antique city site found in Galatepe, about 45 km to the east of Tigranakert, where 3 earthen and 14 pot burials were excavated. No coins were found in any of the tombs.

In the South Caucasus, tombs are one of the main “suppliers” of Hellenistic, Roman, and local coinage, and, thanks to excavations in recent decades, their number must have increased significantly throughout the region. A complex study, including South Caucasian tomb materials, could be prospective from the point of view of the study of political, economic, social, cultural, and ethnic relationships.

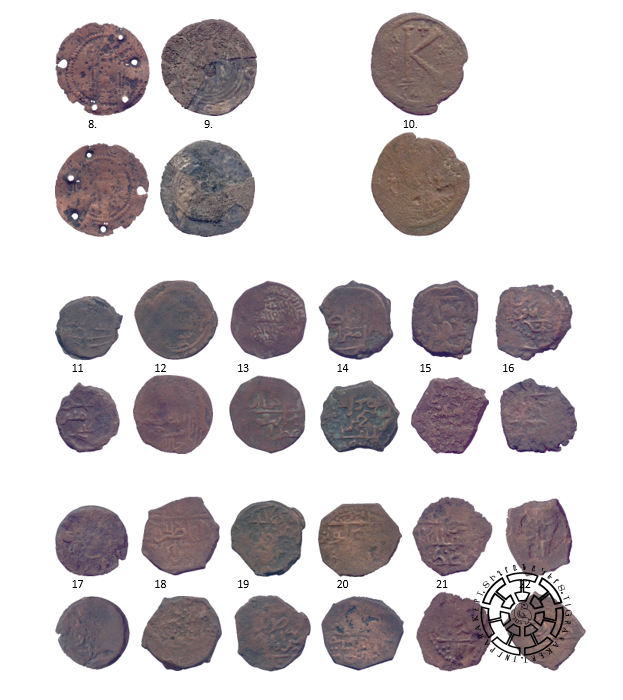

Medieval coins

Tigranakert, being located in the neighborhood of the capital of Aghvank, Partaw, occupying a border position between Iran and Alan’s Doors (Derbend), preserved its strategic and economic importance in the Middle Ages, in the VI-XIII centuries. Tigranakert was a point of border importance under Sasanian rule, which explains the small number of early medieval coins here: two Sasanian and one Byzantine coin. In that historical period, there were not many cities, and the commodity market was not sufficiently developed.

The copper coin of the Sasanian king Kavad I (488-496, 499-531 AD) is badly worn out, but what can be seen from the iconography, as well as the unusual thinness of the flan for a copper coin, allow us to conclude that it is an imitation. (Fig. 5.8). After Kavad came to power for the second time, Armenia again became a Marzpanate. During his reign, the kingdoms of Georgia and Aghvank were also liquidated. Ibn al-Asir writes, ”Then Kavad… built the city of Bailakan in Aran and Partaw (Barda), which is the (chief) city of the entire border zone.” The first issues of Kavad I with the mint names ARM (Armenia) and ARAN (Aghvank) are dated to the 35th year. Five holes are made on the rim of the copper “coin.” It was probably used as a costume ornament.

The other Sassanian coin found in Tigranakert is of silver. It is in a very worn state, but from some of the details, it can be judged that it is a late Sasanian issue, most likely of Khosrow II (590-628; Fig. 5.9).

In the Central Quarter of Tigranakert, near the big church, a copper coin of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I with a nominal value of 20 numia was found (Fig. 5.10). It was struck in Carthage, in the XII year of the emperor’s reign (538 AD). The presence of Byzantine coins here may be the result of the Persian-Byzantine wars that took place during the reign of Emperor Justinian and King Kavad, rather than trade and economic ties.

No coins of the Arab caliphate are known from Tigranakert to this day, despite the fact that not far from there was the center of Aghvank, the city of Partaw/Barda, where the Arabs minted a large number of silver and copper coins.

Studies show that a significant part of the coins found during the excavations of large medieval settlements are usually copper issues, which is a characteristic feature of the city as a center of trade and crafts. This is also evidenced by the composition of monetary finds during the excavations of the Central Quarter of Tigranakert. They are copper coins issued by Ildegizid rulers. Two of the coins are issues of Atabek Shams ad-Din Ildegiz (1136-1175), the founder of that dynasty (Fig. 5.11-12). The residence of the latter was the city of Partaw/Barda on the banks of the Terter River. The remaining 12 coins are copper issues of Atabek Nusrat ad-Din Abu Bakr (1191-1211) (Fig. 5.13-22 and Fig․ 6.23-25). After Jahan Pahlevan’s death, the territory of the Ildegizids was divided between his sons, from whom Abu Bakr got Aghvank, and several adjacent territories. His main residence was Gandzak, not far from Tigranakert. This circumstance likely explains the abundance of Abu Bakr coins in the city of Artsakh. It is noteworthy that 13 of the 14 Ildegizid coins were found in the central quarter, around the church, from depths of 0 to 3.5 meters.

The only silver coin of this period found in the excavations is the dirham of Kai Kobad ibn Kai Khosrov, Sultan of Rum (1219-1236; Fig. 6.26).

After the Seljuks, there was a long interruption in money circulation. It is interesting that Mongol coins from the XIII–XVI centuries were not found, a fact that corresponds to the conclusion of the archaeological research that the upper limit of the dating of medieval archaeological finds in Tigranakert is the first half of the XIII century.

Coins of modern times

The next group of coins already refers to the XVIII century and is represented by one silver issue of the Khanate of Ganja (Fig. 6.27) minted in Ganja and three copper issues of the Khanate of Karabakh minted in Panahabad. The coins were found in different parts of the ancient site.

East of the walled area of the city, in the vicinity of the spring at the foot of the mountaincopper coins of the Russian Empire of the XIX century and the beginning of the XX century were found during the excavations (Fig. 6.31-33).