Excavations

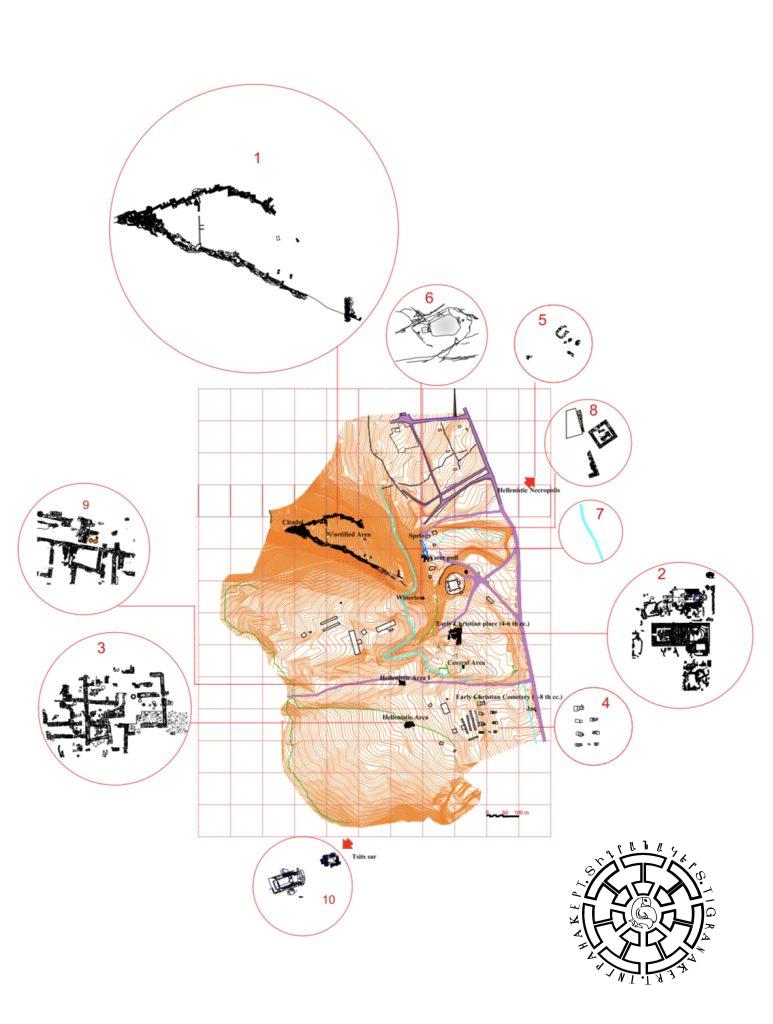

The excavations of Tigranakert conducted between 2006-2020 (Fig. 1) uncovered several significant findings, including: the upper part of the Citadel of the Antique Fortified Quarter; the 83-meter-long defense-headwall separating the Citadel from the quarter; the rock-carved foundations of the southern walls of the same quarter stretching for 450 meters; the northern defense walls up to 5 meters high, and the section stretching about 345 meters; about 40 meters of the south-eastern defense wall; the Antique First Quarter; the rock-carved winepress, the pool next to the Royal Springs; the early Christian Square of the Central Quarter with two churches; the remains of the monument with a cross depiction , and the early Christian graveyard. Partially excavated: one of the antique pithos burial mounds (the eastern burial mound); the remains of the Post Building built in the 19th century; the Second Antique Quarter. An early Christian reliquary and a chapel were excavated on the top of Tsitssar. Excavations of the Fortified Quarter, the Antique Quarters, the Eastern Cemetery, and the early Christian Square were particularly important for understanding the main complexes of the city.

1. Antique or Late Hellenistic Fortified district (1st c. BC.) and Citadel, 2. Early Christian Square with remnants of two churches, a memorial stele, an Early Christian underground reliquary-sepulcher and a graveyard, 3. First Late Hellenistic district, 4. Early Christian cemetery, 5. Late Hellenistic cemetery with jar and cist burials, 6. Rock cut wine press,

7. Royal springs, 8. 18th c. AD mosque and water pull, 9. Second Late Hellenistic district,

10. Tsitssars sanctuaries.

For the clarification of the identity of Tigranakert, starting from the very first steps of exploration, the more than 450-meter rock-carved traces of the defense wall foundations stretching up to the southern edge of the Mount Vankasar slope gained special importance. Their clearly visible stair-like parts were mistakenly considered by Azerbaijani researchers for the stairs leading to the 7th-century church on the top of Vankasar, a circumstance that prevented the discovery of the city.

Excavations (Fig. 2) have revealed detailed information indicating that the most naturally impregnable parts of the cliff were initially chosen for construction. The design of the future wall involved consecutive round (sometimes semi-circular, depending on location) and rectangular towers connected by a zigzag wall. The foundations were leveled, and the external and internal ribbon-shaped parts of the fence were delineated and dug. Bases were then prepared for the first row of blocks. These bases were filled with lime mortar, and the blocks were set into place. The gap between the outer and inner rows was filled with rough-cut smaller stones, and their joints were filled with lime mortar.

Excavations of the northern wall (Fig. 3) revealed that it was basically preserved with up to six horizontal rows of blocks. The excavations provided insight into the technical principles of the construction and block layout, including rustic or pillow-like blocks and facettes (slanted cuts to the outer edges of the blocks). The blocks were either simply placed upon each other or connected with additional connections—the so-called “swallow-tail” connections—which served as a means for seismic stability. Other methods included raising the rows to the ends and using a polygonal layout. Lime mortar was used to fill the defense wall and connect the edges of the rock foundation.

Excavations of the two antique quarters (Fig. 4) unveiled regular multi-sectioned residential-economic complexes with a straight plan, often featuring flattened floors, and facilities for crafts and bread processing.

Excavations also uncovered sections of a reinforced wall supporting the citadel’s terrace, as well as an early medieval wall sitting on a “swallow-tail” wall and traces of dwellings with ovens alongside the defense walls. In fact, in the early middle ages, efforts were made to maintain the citadel’s military capabilities, and particularly, from the 11th–12th centuries, its military significance waned. Excavations in the upper part of the citadel indicate its transformation into a densely populated district during the 12th and 13th centuries. At the same time, the foundations of antique monumental buildings can be verified. Moreover, it can already be stated that not only the defense walls but all the antique buildings were carved out of rock.

Excavations of the Antique Eastern graveyard (Fig. 5) were particularly noteworthy for elucidating the phenomenon of pithos burials. They enabled the restoration of burial rituals, the identification of property assortments, and the discovery of pottery vessels adorned with unique pictorial motifs.

From the inception of the archaeological research, the expedition also accorded special attention to the medieval remnants of the city. During the 2005 survey of the site, it became evident that the material traces of medieval culture were abundantly visible in a flat area extending from the late medieval castle to the southeast, covering approximately seven hectares and rising 4-6 meters above the surroundings. It was evident that this elevation was artificially created over centuries of cultural activity. Conditionally referred to as the Central Quarter (owning its intermediate position relative to the Fortified Quarter, early Christian cemetery, Antique Quarter, and late medieval castle, seemingly surrounded by them), the entire area of this quarter featured conspicuous stone structures, diverse architectural fragments, ovens, wells, and hundreds of plain and glazed pottery sherds.

As a result of the excavations of 2006–2020 (Fig. 6), various church structures and the remnants of stelae were discovered, along with the residential-economic complexes dating from the 9th–11th and 12th–13th centuries. Additionally, numerous agricultural tools, coins, jewelry, and thousands of specimens of unglazed and glazed pottery and glass were found.