Tigranakert in written sources

Naming cities after dynastic figures was a common practice in the Hellenistic world as a result of Alexander the Great’s conquests. Numerous Alexandrias, Seleucias, and Antiochs were established in homage to the Hellenistic monarchs. In Armenia, a similar trend existed, with many cities bearing the names of kings predating Tigranes the Great. Examples include Yervandashat, Yervandakert, Arshamashat, Artashat, and several cities with names like Zarehavan and Zarishat. These newly founded cities often followed the principal known synoecism, or cohabitation, where the kings forcibly relocated merchants and craftsmen from various cities and countries to settle in the newly established city, ensuring its diverse and functional population. As a result, these cities were typically multinational in nature.

This tradition gained further momentum in the reign of Tigranes the Great (95-55 BC) as his significant achievements created increased opportunities for wealth, labor, and synoecism. Besides the renowned capital Tigranakert, founded in Aghdznik, which was praised by many Greco-Roman historians (Strabo, Appian, and Plutarch), there are several other settlements bearing Tigranes’ name known in historical Armenia and abroad. For instance: Tigranakert town in Goghtn, Tigrana settlement in Media, and Tigranukome in Amanos. It should be noted that the exact location of these settlements, including the capital, Tigranakert, is unknown.

The 7th-century Armenian historian Sebeos, describing the Byzantine emperor Heraclius’ (622-624) Persian invasion, mentions two settlements named Tigranakert that can be included among these settlements. He recounts an episode during the war when the Byzantine emperor attempted to escape the pursuing Persians by crossing from the Armenian province of Syunik to Iberia. However, a Persian army descending to the plain from Gardman intercepted him near the “other Tigranakert.” The emperor tried to retreat along his path but encountered another group of soldiers at the “avan of Tigranakert.”Thus, Sebeos refers to two Tigranakerts, one of which he labels as “other,” located in the north, and the “avan” of Tigranakert in the south. Persumably, the author calls one of the Tigranakerts “the other” to distinguish it from the “avan” of Tigranakert.Sebeos typically employs the term ‘avan’ to denote a fortified settlement, which may be enclosed by walls or situated adjacent to or surrounding a fortress. This information is absolutely reliable, as the authors mention these settlements as the places of Heraclius’ military maneuvers unrelated to the reign of Tigranes the Great or events from his period. Sebeos’ account strongly suggests that in the early 7th century, Artsakh and Utik housed two settlements named Tigranakert. Given that the emperor’s army needed to traverse the main road to urgently reach Iberia (Eastern Georgia), it is highly likely that these two Tigranakerts were situated in close proximity, possibly along or near the northern route, on the incline of the Artsakh Mountains and the Utik plain.

The famous Greek historian Strabo mentions in one of his writings the capital Tigranakert, saying that “Tigranes founded a city near Iberia, between this place and Zeugma on the bank of the Euphrates. Gathering here the population of the twelve Greek cities he had destroyed, he named the city Tigranakert.” It is plausible that Strabo’s account of the location of the capital Tigranakert may have been conflated with information about other Tigranakerts. As noticed by the renowned historian Giusto Traina, the Tigranakert near Iberia could possibly be identified with the Tigranakert of Artsakh.

According to Movses Kaghankatvatsi, a 7th-century Armenian historian, the army of Heraclius on its way to Tpghis (modern-day Tbilisi) first halted on the bank of a ravine, south of the river Trtu (now Tartar), near the village of Kaghankatuyk. Then it made another stop near the village of Dyutakan, adjacent to the Trtu torrent. By examining this and other pieces of information provided by Kagankatvatsi, it can be deduced that the southern Tigranakert mentioned by Sebeos, known as Tigranakert avan, was situated south of Tartar, not very far from Partav, marking the end of the Artsakh Mountains and the beginning of Utik’s steppe. While Movses Kaghankatvatsi does not explicitly mention any Tigranakert in this part of his history, a letter about a meeting convened by the Armenian Catholicos Yeghia in Partav in the early 8th century, which is also included in the history known by the name of Kagankatvatsi, states that, among others, the meeting was attended by the monk Davit from Kaghankatuyk and the monk Petros from Tkrakert (in this case likely a priest). First, it can be assumed that Tkrakert is the local pronunciation of Tigranakert; second, it was probably located not far from Kaghankatuyk, as it is mentioned immediately after it. Therefore, it is likely to refer again to Tigranakert avan, or Tigranakert of Artsakh. The role of Tigranakert as an important settlement at that time is further evidenced by the construction of a cruciform central dome church at the end of the 7th century atop a mountain just a few hundred meters from the settlement. Excavations of Tigranakert Central Quarter revealed remnants of a basilica church dating back to the 5th and 6th centuries. It is believed that Petros was the priest of this church.

In the period of the strengthening of the Khachen Principality in the 12th and 13th centuries, when the borders of Hasan Jalal’s rule reached the River Kur (Kura), the foothills and plains of the Khachenaget valley were referred to as Tigranakert, named after the city of Tigranakert. A 13th-century inscription in the Koshik Anapat (hermitage) near one of the tributaries of the upper stream of Khachenaget mentions the land of Tigranakert, from which a certain man named Hakob donated to the monastery. The fact that Tigranakert was a large settlement at that time is evidenced by the excavations in the Central Quarter, which revealed a rich urban culture dating back to the 12th and 13th centuries.

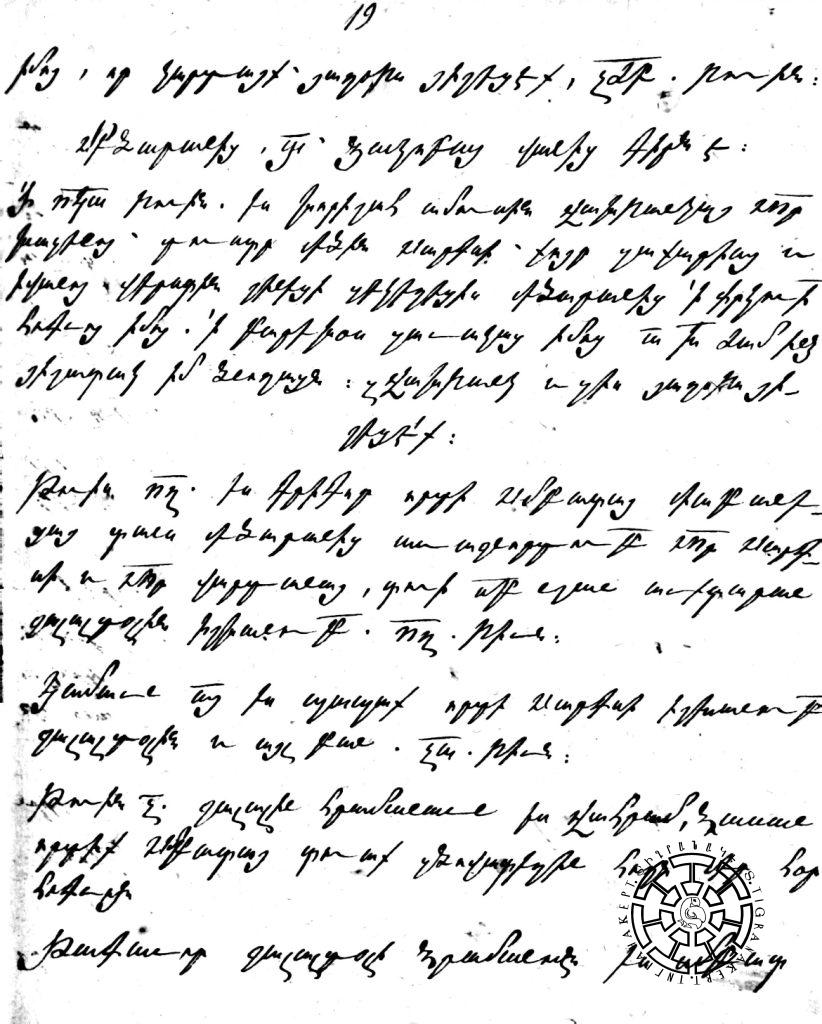

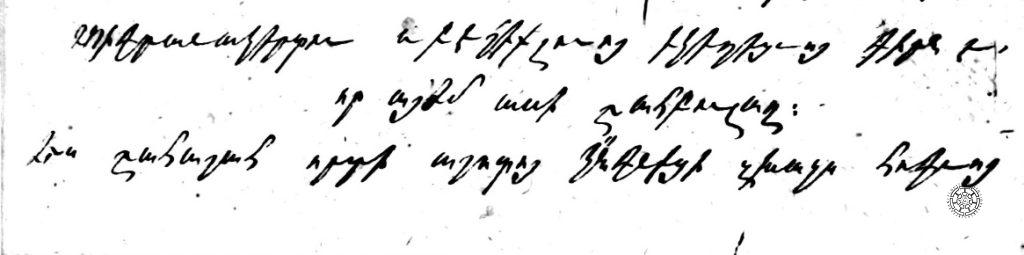

Chronologically, later information pertains to the ruins of Tigranakert or the city site, serving as the basis for today’s search for traces of the city. Thus, Catholicos Yesai Hasan-Jalalyan, residing in the Gandzasar monastery (located on the same bank of Khachenaget as Tigranakert, but in the upper valley of the river and on its left bank), described himself as an eyewitness to the destructive Lezgins raid on Artsakh in the early 18th century. He wrote that the conquerors, seizing people and cattle and “leaving from Tkrakert, they set up an army on the banks of the Drdu River, which we now call Tartar”. It is highly likely that the raiders concentrated the looting of the Khachen Valley in Tkrakert-Tigranakert due to the presence of watery springs in this area. Another significant testimony (Fig. 2) comes from the lithographic diary of the Catholicos. “It is the inscription of Tigranakert and Beshiklu church (i.e., the church of Vankasar) that is now called Shahbulagh. “Ես Շահաշահ որդի Աշոտոյ կ[ա]նգնեցի զխաչս հոգւոյ /իմոյ, որ կարդայք` յաղօթս յիշեցէք, :ՉԺԲ: (1263 թ.) թուին [I, Ashot, the son of Shahashah, erected this cross for my soul, if you will read it, would remember me in (your) prayers, in (Areninan year) 712 (1263 A. D.)]”. In fact, the Catholicos confirms that the church of Vankasar is located in Tigranakert and that this area is identical with Shahbulagh or the Royal Springs.

In the middle of the 18th century, Panah, the fierce enemy of the Artsakh Melikdoms, constructed a fortress next to the Royal Springs (later called Shahbulagh). Sargis Jalalyants, who visited these ruins in the mid-19th century, reported that the Armenians called the area around the Shahbulagh springs ‘’Tngrnakert,’’ while the Persians called it Tarnagirt. He assumed that Tigranakert had been located precisely here. A similar viewpoint and information were expressed by the Artsakh antiquities researcher Makar Barkhubaryants, who additionally noted that the lower valley of Khachenaget was referred to as Tigranakert province.

In 1952, S. Yeremyan placed Tigranakert of Artsakh near Aghdam in the atlas of the book “History of the Armenian People.” In the late 1950s, a sarcophagus (stone coffin) lid with a large Armenian inscription was found during agricultural activities in an archeological site called Gyavurkala (near the village of Sofulu, in the Aghdam region of the former AzSSR), eight kilometers away from Shahbulagh. The Academy of Azerbaijan conducted urgent excavations here, and the text of the inscription was published by Sedrak Barkhudaryan, who at that time was busy compiling an academic volume of the Artsakh inscriptions. As a result of excavations, a large fortified settlement, an early Christian church, a large cemetery, etc. were discovered. Sedrak Barkhudaryan, taking into account the existence of such a large settlement not far from Shahbulagh, considered it possible that Tigranakert must be searched not right in the surroundings of the springs but in the territory of Gyavurkala. For the Azerbaijani opponents’ information, who think that once Azerbaijani archeologists have researched these areas in detail and declared responsibly that no Tigranakert ever existed here, the researcher of Gyavurkala, well-known Azerbaijani archeologist R. Vahidov, also situated Tigranakert around Shahbulagh. In his Azerbaijani article published in 1965 dedicated to the excavations of Gyavurkala, he disputes Sedrak Barkhudaryans’ opinion and literally writes the following: “Yeremyan’s testimony that Tigranakert was found near Aghdam is beyond doubt.”

Judging from the attached map to his book “Episodes of History of the Armenian Eastern Side,” published in Yerevan in 1981, Bagrat Ulubabyan placed Tigranakert of Artsakh in the inner valley of the River Karkar.

On this occasion, the researcher of Artsakh monuments, Samvel Karapetyan, has written that the researchers have located Tigranakert of Artsakh “to the north-east of Shahbulagh fortress: in the area of the famous spring and the present Tarnoyut (Tarnagyut) village (at the foot of Vankasar) or in the territory of Gyavurghala city.”

There is also confusion on the issue of Tigranakert location in the recently published “The Monuments of Vankasar” article by H. Simonyan and H. Sanamyan. Although the authors have described the surroundings of Shahbulagh, the settlement is mentioned twice with the name Gyavurkala-Tigranakert.

The expedition, undertaking a comprehensive study of Khachenaget’s lower valley, aims to make the presence or absence of the ancient city archaeologically provable. As a result of that exploration, the overground traces of the city built by Tigranes the Great were discovered, further excavations of which finally and visibly confirmed the fact of the existence of a large and rich ancient city.