The disc with Armenian inscriptions

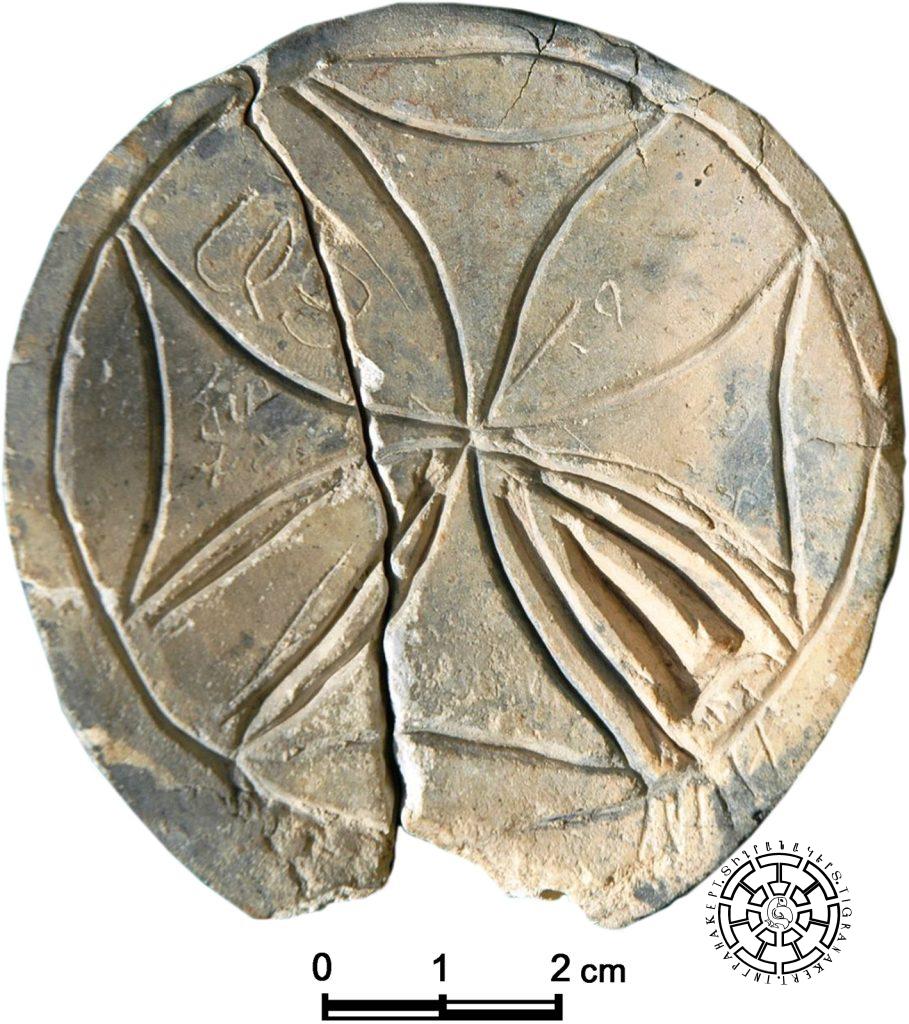

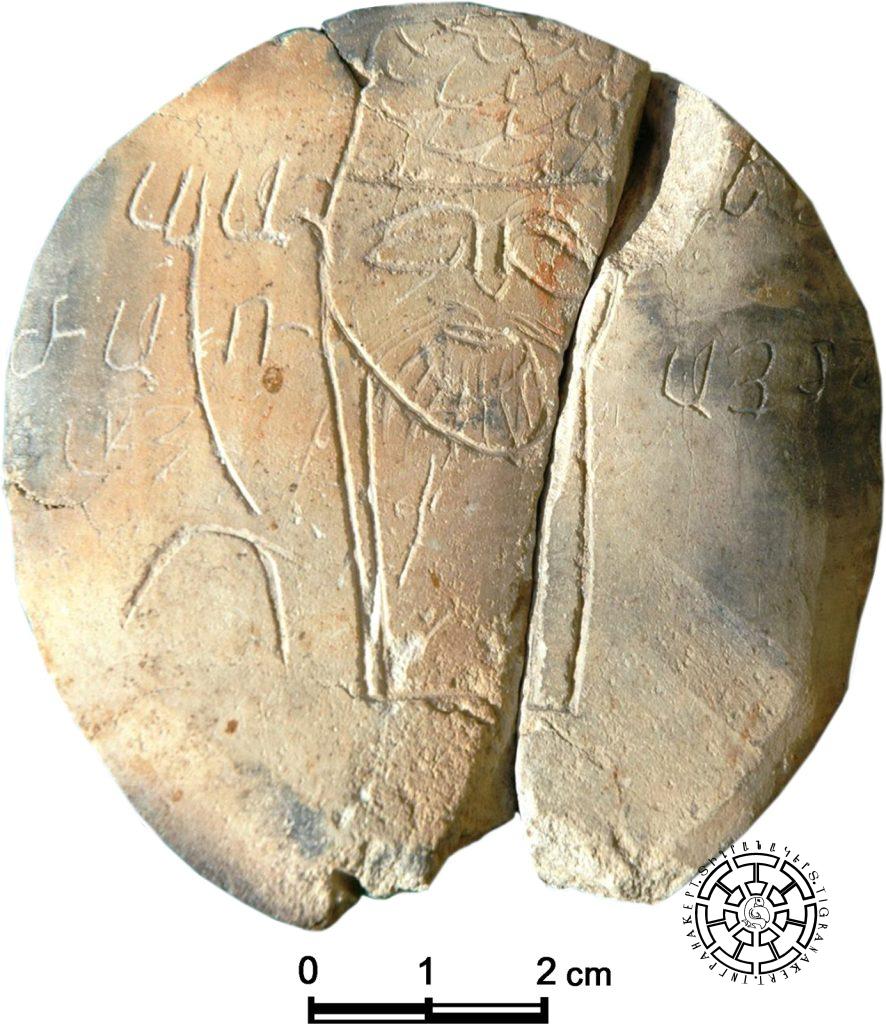

Among the archaeological findings of Tigranakert, the small clay disc (diameter 7.5-7.8 cm, thickness 0.5-1.0 cm) found on July 19, 2008, during the excavations of the large church of the Early Christian Square is of particular importance. On one side of it is carved an encircled semi-winged cross (Fig. 1), and on the other side is a portrait of a man with a mustache and beard wearing a fur hat (Fig. 2). The Armenian inscriptions engraved on the disc are already important evidence of the early medieval Armenian identity of the church, the city, and, more broadly, the inner valley of the Khachenaget River. The second importance of this invention is purely archaeological-cultural and relates to the uniqueness of the find and its function.

The disc was found at the pavement level of the church, about two meters west of the first north entrance, under the north wall, divided into two parts. The fracture is old, suggesting that it fell onto the pavement from some height. As a result, it split in two and lost a small fragment. It is likely that it was originally placed in the wall, perhaps in a special cavity or built-in shelf (since the presence of cracks is excluded in walls lined with smooth-polished, tightly pressed slabs). In the end, it fell into a fire, as a result of which it became covered with smoke in places.

The disc was crafted from well-sifted, unbleached, high-quality whitish clay (kaolin), and after firing, it obtained a whitish-yellowish hue. While still wet, two through-holes (only one preserved, the second probably found on a lost fragment) were punched on one edge, which relate to its function. The disc was then polished, covered with an engobe made of the same clay, and polished. The edges were smoothed with a sharp knife-like tool. The engravings were made on wet clay, probably with the help of metal pens. Moreover, judging from the carved individual components, two different tools were used. One of them had a cutting blade, and the other had a thin, rounded tip. With the help of a blade, the cruciform composition, with triangular grooves in the section, was created, and with a rounded tip, the portrait and inscriptions were carved. After engraving, the disc was fired, as a result of which it was deformed: the face bearing the portrait became convex, while the cross-decorated face became concave.

On the convex obverse of the disc (Fig. 3a) is engraved a man’s bust: right shoulder, stretched neck, straight face (in face). Covering the head and forehead is a hat (we assume fur, perhaps sheepskin) trimmed with horizontal waves of short bows. The eyes are oval, the nose is short and regular, the mustache is of medium length, and the beard is short. The engraving is schematic, and it is difficult to see any distinct individual lines underneath. It’s another way that a hat, mustache, and beard can indicate a certain status.

On the concave reverse (Fig. 3b) the classical composition of a cross within a circle, which is one of the most common themes of early Christian iconography, is engraved. It is very popular in Armenian monuments, especially in the 5th and 6th centuries. Parts of stone discs with similar designs were found in the excavations of the same church in Tigranakert; they were also carved in the rock-carved worship complex near Tigranakert, on the bank of Khachenaget.

Placing a portrait (usually a half-face) on one side and a religious symbol on the other was a very common phenomenon in ancient Byzantine, Sassanid, and many other monetary systems. Therefore, we can assume with high probability that our disc could have any dram as a general example. And if we consider the obvious Sassanid style of the portrait, it is even probable that it was influenced by the Sassanid drams, undoubtedly, except for the specific iconography of the cross and the Armenian writings.

The disc has Armenian inscriptions on both sides. The writings are brief, and the number of letters is limited. However, a general idea about fonts can be made. The inscriptions are engraved with Bolorgir-a type of Armenian script, a modified version of small Yerkatagir letters (steel letters or iron letters-it is a lithographic script; it was written on a stone with an iron tool, from which it got the name iron script). The letters are not proportional; the classical proportion is not always preserved. They were carved on wet clay without a preliminary outline of the lines, in which case it would have been technically difficult to avoid such deviations. The calligraphic features of the letters are similar to a number of inscriptions from the 5th-7th centuries (Tekor, Jerusalem, Aruch, Mastara, Mren, and Zvartnots). The antiquity of our inscription is also not contradicted by the titles, the first examples of which are known from the 6th century at the latest (for example, in the mosaics of Jerusalem).

Some samples of Armenian letters have been preserved among the signs of the masters (Գ, Զ, Թ, Ճ, Մ, Ո-G, Z, T, Čh, M, O) carved on the stones of the small central dome church built in the 7th century on the top of Vankasar, but they were indiscriminately executed with rectilinear Yerkatagir. The Armenian inscriptions of the rock-carved complex on the Khachenaget bank are also noteworthy, this time carved in Bolorgir script. Unfortunately, the well-known Gyavurkala inscription is not comparable to our inscriptions, which, although they are made with the Bolorgir type of Yerkatagir script, the strongly stretched letterforms and the abundance of inscriptions indicate a completely different style and time. From these enumerations, it can also be concluded that the inner valley of Khachenaget is quite rich in early Armenian inscriptions.

On the cross-carved face of the disc, between the upper vertical and left horizontal wings of the cross, “AY” is engraved, which is an abbreviation of the word “Astutsoy” (“God” in Armenian).

The main inscription is engraved on the obverse, on both sides of the face. Three lines are engraved on the left and two lines on the right. The letters of the first two lines (both left and right) are carved with a groove, while the letters of the third line are made with a hairline and appear to be added later.

The inscription can be read in two ways. In the first case, we will have «ԵՍ/ ՎԱՉԷ/ ԾԱՌԱՅ Տ[ԵԱՌ]Ն/ Ա[ՍՏՈՒԾՈ]Յ» (I/ VACHE/ SERVANT OF LORD”); in the second case, «ԵՍ/ ՎԱՉ[ԱԳԱՆ]/ ԾԱՌԱՅ Տ[ԵԱՌ]Ն/ Ա[ՍՏՈՒԾՈ]Յ» (“I/ VACH[AGAN]/ SERVANT OF LORD”),

If we keep in mind that the last word “Ա[ՍՏՈՒԾՈ]Յ (Astutsoy-Lord) is most likely a later addition, then the inscription had the following preview:

«ԵՍ/ ՎԱՉ[Է]/ ԾԱՌԱՅ Տ[ԵԱՌ]Ն¦»

Or:

«ԵՍ/ ՎԱՉ[ԱԳԱՆ]/ ԾԱՌԱՅ Տ[ԵԱՌ]Ն»

(“I/VACH[E]/SERVANT OF GOD”)

Or:

“I/VACH[AGAN]/ SERVANT OF GOD”

Now a few words about the possible use of the disc. At first, when we did not notice the through hole made at the bottom of the disc (the inside of the disc in its position when the portrait is vertical and the inscriptions have a horizontal legible position), we considered the possibility that it was an offering made by the believers to the church with memorial inscriptions. A phenomenon that was widespread in early Christianity. However, the regular hole made in advance makes another assumption more likely. The disc was attached to something (for example, a package, a box, etc.) by means of a thread passed through that hole (perhaps two holes, only one of which has been preserved); that is, it acted as a seal. The disc could not be hung from any protrusion through that hole, nor could it be hung from the neck, as both the portrait and the inscriptions would then be upside down for the viewer. The fact that the disc is made of clay and fired is completely consistent with this assumption.

Referring again to the personal name Vache or Vachagan in the inscription, we should note that both personal names are quite well known from the history of Kaghankatvatsi and partially from other early medieval Armenian sources. At least two Vache and four Vachagan are known. Vachagan Brave Arshakuni and his successor, Vache the First, are far more mythical than real personages. Apart from the name, no information is known about Vachagan the Second (he is remembered by Kaghankatvatsi as Yavchagan). The most famous are the kings Brave Vache, who supposedly lived in the sixties of the fifth century, and Vachagan the Pious, who reigned in the late fifth and early sixth centuries, the latter being the nephew of the former. The extensive stories about them found in Kaghanakvatsi’s history have had various interpretations, up to doubts about their being a historical person. In our case, it is remarkable that the historian presents both of them more as merciful Christians than as rulers. The fourth Vachagan, of whom only one mention survives, was active in the eighth century. The historian remembers him in connection with the raid of the Arabs on Khazirk in 714 as “Brave, vigorous, prosperous archer yeranshahik (Aranshahiks or Yeranshahiks, an Armenian princely royal family in Utik and Artsakh provinces of the Great Armenia) Vachagan Patrikean prince of Aghvank.”

The archaeological environment of the find’s discovery (it was found on the pavement of the church built in the 5th-6th centuries, in the middle of the hall, next to the northern wall), the iconography of the cross, and the lettering of the inscriptions give the basis for dating the disc to the end of the 5th century at the earliest and the beginning of the 7th century at the latest.

According to the legendary conversations in the History of Kaghankatvatsi, if Vache II renounced the kingdom, took the gospel, and entered a monastery, then Vachagan the Pious was engaged in collecting the relics of saints and convening church meetings, the most famous of which was the meeting of Aghven. In other words, in the life of Vachagan the Pious, there were many situations when church documents or boxes could be authenticated with the royal “stamp.” And it was in such cases that the king could act with a not secular but ecclesiastical “title series.”

This find of Tigranakert is actually one of the oldest Armenian inscriptions found in the territory of Artsakh and is the best argument for the early Christian-Armenian face of the Khachenaget inner valley, which was outlined by the data of numerous other historical sources even before this discovery.