The Canal

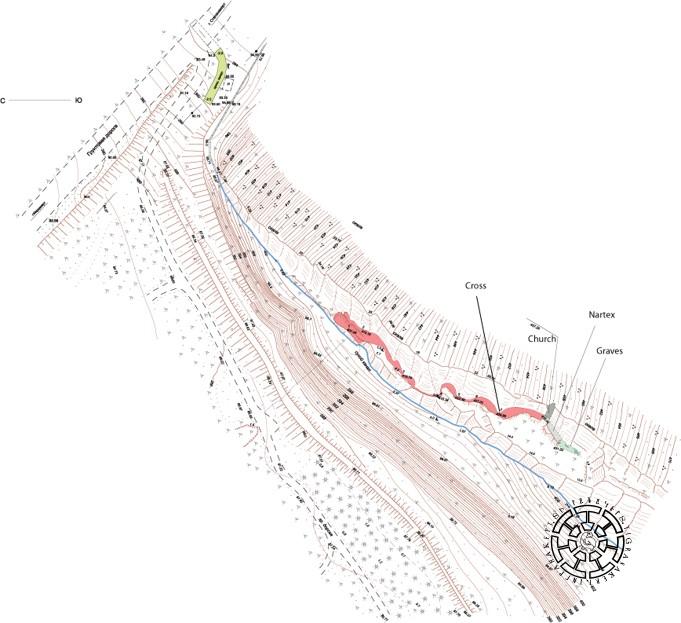

The canal of Tigranakert in Artsakh is one of the largest and most technically complex hydraulic structures in historical Armenia (Fig. 1). It starts from the Khachenaget River (Fig. 2), about 3.3 km northwest of the main city.

It passes along the lower part of the northern slope of Vankasar, parallel to the river (Fig. 3), then directly at the foot of the cave-cultic complex (Fig. 4). From there, it exits the steppe, turns towards Tigranakert, bordering Vankasar from the south, and passes directly at the foot of the Fortified Quarter, where some sections are carved into the rock again (Fig. 5). Continuing its course, it traverses the Second Antique Quarter, circumvents the Central Quarter, and flows into the steppe. At the foot of the cave-cultic complex, the 500-meter-long canal passes through a rock-carved section, which also has two tunnel parts (Figs. 6, 7).

The archeological survey of the canal was carried out in 2006 and 2020. As a result, the entire trajectory of the canal was outlined. The approximate location of the start point from Khachenaget was determined, shedding light on its origin. A 300-meter section of the rock-cut part of the canal was excavated, and the technical structure of the main watercourse was clarified. Research on the rock-carved sections, including traceological analysis, was carried out. Signs carved on the walls were validated, photographed, and measured. The walls of the open sections of the canal were made with stone and mortar. Among them, sections with a height of 0.3-0.5 meters are preserved (Fig. 8). The width of the watercourse itself varies in different places, ranging from 1 meter in open areas to 1.5-2.0 meters in tunnel sections. In the open area, the floor was reinforced with a pressed layer of flat limestone burrs (Fig. 9) to reduce water loss on the soil base. At the same time, rock-carved sections and soil-based sections were often combined.

Fig. 8 The rock-carved part of the canal with the traces of the side walls.

Fig. 9 Cut out of the flattened floor of the canal.

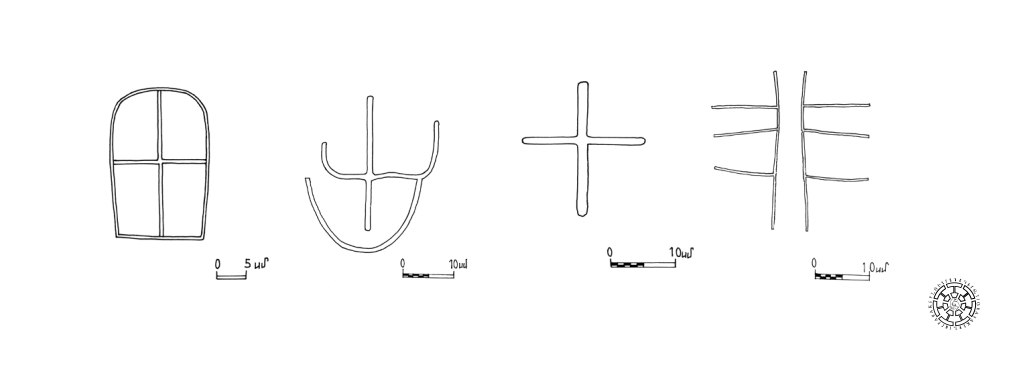

As revealed by the traceological research of the rock walls, which was carried out by the specialists of the University of Florence, two types of quarry tools were used to process the rocks: pointed heavy hammers and broad-bladed pickaxes. In this respect, the channel tracery differs from the traces of the Fortified Quarter and early Christian structures, which indicate the use of grinding-smoothing tools. Several primitive images of crosses were preserved on the walls of the canal that can be dated to the 6th-7th centuries (Fig. 10).

The second section of the tunnel was explored by the 2020 excavations. It includes one large and two small tunnels dug into the rock, forming its continuation, the total length of which is 10.5 meters (Figs. 11, 12). As a result of the excavations, the presence of the outer rock-carved wall of the canal was confirmed once again. Here, the canal has a width of 1.5 meters in its narrowest part and 2 meters in its widest part. The height of the rock tunnel was 0.8 meters. The rocky bottom of the canal was covered with a 20-30 cm-thick sand sediment layer.

The results of this complex research, along with comparisons to the technical data on the Tigranakert Fortified Quarter and the cave-worship rock-carved complex, suggest the following:

a. The canal was built concurrently with the founding of the city.

b. As the city incorporated the Royal Springs as its main source of drinking water, the canal has been increasingly used to irrigate the city’s extensive agricultural suburbs as well as for domestic purposes.

c. The canal operated throughout the city’s existence until the mid-13th century. It was then reopened in the middle of the 19th century and experienced intermittent use during the Soviet era. These periods of use and disuse contributed to the unique archaeological findings uncovered during the canal’s excavations, including several sherds and three fragments of an indeterminate iron tool.