Tsitssar

Tsitssar is located in the eastern part of Tigranakert, south of Vankasar, at an elevation of 610 meters above sea level. Prior to the 2019 archaeological excavations, exploratory works were carried out in the elongated part of the mountain’s summit. These efforts confirmed the presence of traces of fence walls and rock-hewn pits intended for obelisks, smoothly polished stones, fragments of jagged cornice, and remains of structures, among other findings. Visually, the foundations of a dry-laying defensive structure and traces of at least three ritual structures, longitudinally edging the north-south ridge of the mountain summit, are evidenced. In 2019 and 2020, based on the results of exploratory work, the two of those structures-the northern one and partially the southern one (Fig. 1)-were excavated.

THE RELIQUARY

The first structure uncovered during archaeological excavation at the Tsitssar site in Tigranakert is the underground mausoleum-reliquary. It is a 1.70-meter-deep underground structure built by using smoothly polished stones on the interior, irregular stones on the exterior, and lime mortar (Fig. 2). The structure has an east-west orientation. The internal dimensions of the building are 265×210 cm. The floor is located at a depth of 1.70 meters below the current ground level. It was paved and additionally reinforced with lime mortar. The eastern and northern parts of the floor are relatively well preserved.

The mausoleum-reliquary has an entrance on the western side, which is a quadrangular pit lined with smoothly polished stones made of rock and leveled with lime mortar in two steps. The entrance is closed at the top by a fully polished columnar slab of limestone, measuring 120 cm in length and 100 cm in width. The upper, smoothly polished sections of the northern and southern walls of the structure (the core made of limestone rough blocks and lime mortar has been preserved) exhibit inward curvature, suggesting that the structure was vaulted.

The mausoleum-reliquary has five niches, two of which are located in the southern and northern parts of the western wall. The third and fourth niches are situated in the southern and northern walls, respectively. The fifth niche is located in the southern part of the eastern wall. The pits are 80-120 cm deep. Their volume expands inward. The side walls of the niches are smoothly polished, and the floors are leveled with mortar. The covers are constructed using limestone of varying sizes and lime mortar.

The archaeological findings from the mausoleum-reliquary are indeed noteworthy. Among the limited pottery and mostly decayed sherds, several significant discoveries stand out. These include partially complementary pieces of an early medieval clover-shaped wide-mouthed jar retrieved from the damaged niche of the southern wall, as well as three different parts of the complete fragment of antique colored pottery recovered from different sections and depths of the structure. Three complementary fragments of a tile, a fragment of green glass, etc. were also unearthed. Among the discovered rough-cut and smooth-cut stone fragments, a 10-cm-long cross-wing fragment of an early medieval winged cross is particularly remarkable.

The discovery under the north wall of the structure presents a unique situation. A corpse was lying in an east-west direction on the floor slab; the deceased was not buried, but the remains were simply placed on the floor. In its initial position, only a part of the ribs, vertebrae, and upper left limb were present; however, parts of the limbs and a piece of the skull were in the southeast part of the structure, beneath the floor slab. The general impression is that we are not dealing with a burial but with a dead person on the floor, whose bones were later scattered across different areas of the floor. It is plausible that these are relics of a saint that were scattered or perhaps concealed under unusual circumstances.

Considering the presence of special niches, the absence of an altar, and its similarity to the reliquary of the Central Quarter of Tigranakert, it is more likely a structure for housing the relics of saints, than a mausoleum. The construction equipment, slabs, design, dimensions, and function give a basis for dating the shrine to the 5th-6th centuries and considering it one of the manifestations of Vachagan Pious’s religious reformers.

THE CHAPEL

The other excavated structure at Tsitssar is situated on the highest part of the mountain, 22 meters south of the mausoleum-reliquary. Archaeological work uncovered a rectangular structure oriented west-east, built with smooth-cut limestone and lime mortar. Only a portion of the southern wall has been preserved from the smooth-cut line, measuring 3.13 meters in length on the outside (6 stones) and 3.40 meters on the inside (7 stones, 2 of which are lying). The wall is 1.20 meters wide. The smooth-cut stones are either lined up on rough foundation stones or leveled rock. In other sections of the structure, only the foundation stones of the walls have been preserved.

In general, the preserved sections reveal an early medieval church with a clear west-east orientation, measuring 8.5 meters in length and 5.15 meters in width (Fig. 3).

The chapel features an altar on the east side, from which a large number of concave chipped stones have been unearthed, indicating the presence of a semicircular dome. The stage for the altar was a carved rock, with a central step made from the same rock for access to the altar. Only two smooth-cut slabs have been preserved from the altar floor, revealing that the altar stood at a height of 0.80 meters from the prayer hall.

The prayer hall itself measures 4.5 meters in length and 2.5 meters in width. The western part of its floor was leveled on the bedrock, while the eastern part continues with rammed loam. Only the southern entrance of the church is clearly visible, as confirmed by the preserved section of the southern wall.

During the archaeological works, a large number of smooth-cut stones were found, including those with a concave surface, fragments of a jagged cornice, etc. Among the crosses unearthed during the excavations are fragments dating back to the 8th-9th centuries. In one example, the cross is depicted on a smooth-carved cornerstone by removing the background; it has single-bud finials and extended upper and inner arms. Among the cross images found are two large and small crosses roughly carved on the front part of the oblong, concave-smooth-cut stone, the fragment with the early medieval equilateral encircled cross. The two sections of the small khachkar dating from the 12th–14th centuries, the fragments of the broken rosette of the same khachkar found on the eastern and southern sides of the church, etc. are noteworthy.

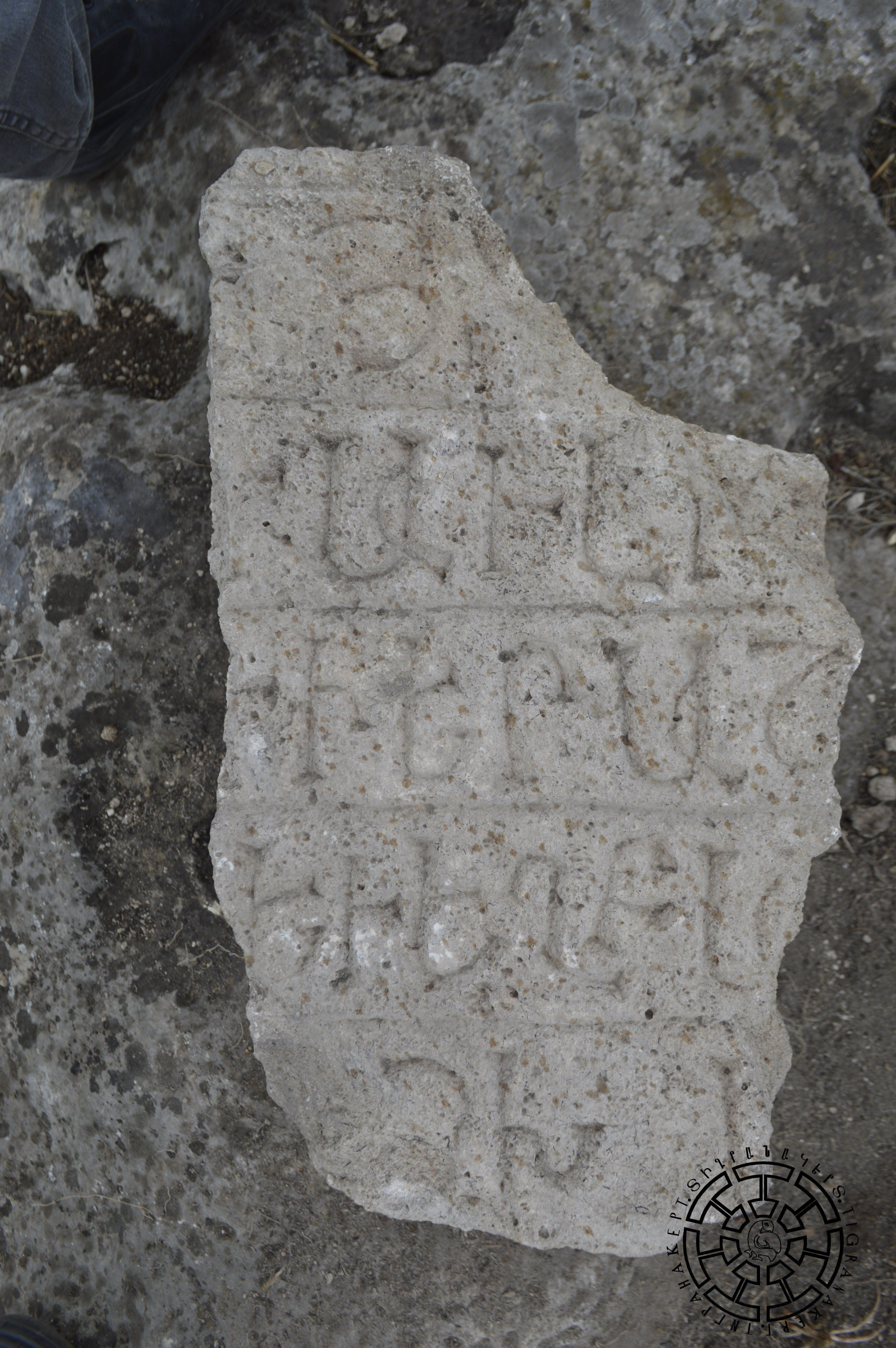

Among the findings, the slab fallen from the southern wall of the church is particularly important, on which a fragment of the Armenian five-line inscription dating from the 11th-13th centuries (according to the letterforms) has been preserved. Both side parts of the slab are broken; as a result, only the central part of the inscription was preserved (Fig. 4). A small fragment of an early medieval inscription was also found.

Antique and medieval pottery was also found during the excavations. There are two fragments of antique colored pottery that are identical in shape to the fragments of an antique colored vessel found in 2019 from the Tsitssar mausoleum-reliquary. Medieval pottery is represented by fragments dating from the 7th-9th, 9th-11th, and 12th-14th centuries, among which a large number of oil lamps of different sizes and shapes stand out (Fig. 5). Three glazed fragments of pottery, fragments of glass vessels, an iron rivet, etc. were also found.

It can be concluded that the chapel was built in the early Middle Ages and functioned until the 14th century. Over time, cross compositions and inscriptions were carved on its walls, and khachkars were erected around it.