Tigranakert and the war

During the 44-day war, Tigranakert became a target of enemy shelling, despite our repeated warnings. As a result, the archaeological camp of Tigranakert was completely destroyed. Artsakh authorities and our research team could not allow Tigranakert Archaeological Museum to suffer such a fate. The museum collections were successfully evacuated to a secure location. The archaeological findings of the Tigranakert excavations are the property of the Artsakh people. The political non-recognition of Artsakh, occupation, and forced displacement cannot diminish its indigenous people’s right to their cultural heritage, including the right to manage their material cultural heritage. The Azerbaijani strategy of depriving the people of Artsakh of their cultural heritage is a continuation of the genocide of Armenian cultural heritage. Genocide, which we have witnessed for decades; genocide, which culminated in the destruction of thousands of khachkars in Jougha (Julfa) in 2005-2006; and cultural genocide, which gained momentum after the 44-day war, became a daily practice after the September 2023 ethnic cleansing of Artsakh. Such actions cannot be justified by fake political statements and artificial accusations. Despite these challenges, our team remains committed to continuing our research, popularizing the cultural heritage of Artsakh, and exposing Azerbaijani vandalism. Aggression, military supremacy, ethnic cleansing, and threats against Armenians are not eligible. They cannot deprive the people of Artsakh of their inherent right to preserve their identity through their cultural heritage.

After the 44-day war, when Tigranakert and its surroundings came under Azerbaijani control, Azerbaijani specialists had the opportunity to observe the results of the excavations. Despite this, claims persist that the Armenians “invented ancient cities” for themselves during the “occupation of Karabakh,” which are situated on Azerbaijani lands. Additionally, it is alleged that the Armenian side conducted “illegal” excavations without involving international experts and lacked serious scientific justifications, along with making changes in place names. The antique Tigranakert, with thousands of squares still intact, stands as a classic example of Hellenistic urban planning and fortification. Its prototype was developed as early as the third century BC in Alexandria, then spread to Asia Minor, reached Armenia, and was first used in Artashat. Here is a part of the English article “Tigranakert of Artsakh,” authored by the expedition leader H. Petrosyan, which was published in the Oxford journal “Aramazd.” (Petrosyan, Hamlet. Tigranakert of Artsakh. Aramazd. Armenian Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 2020.10/1-2. 327-371. https://www.academia.edu/44738770.)

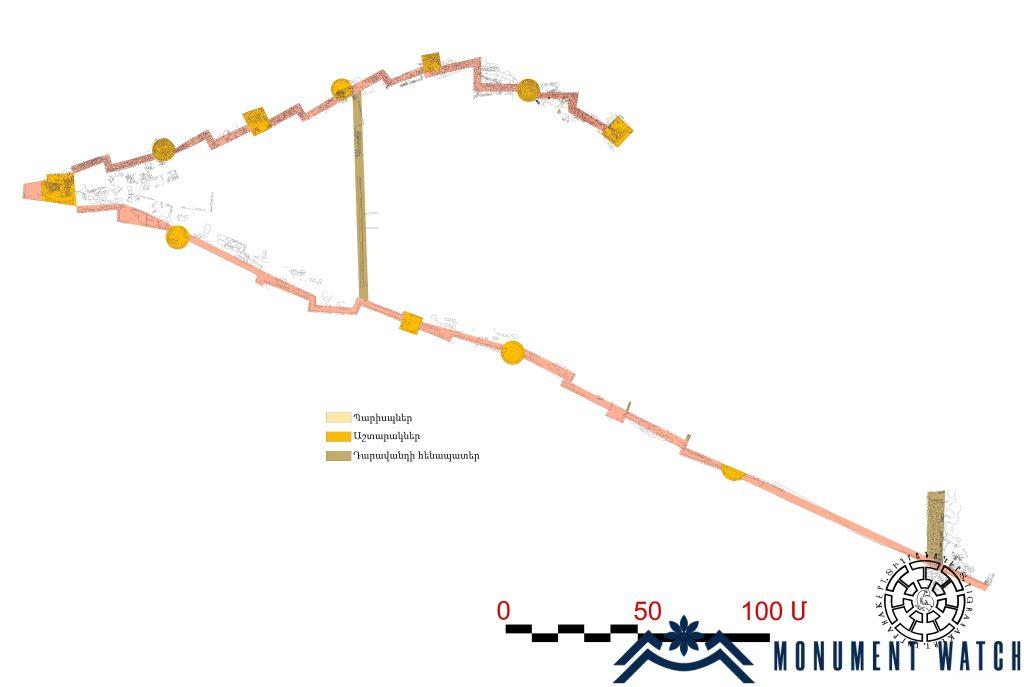

“The fortification system of Tigranakert consists of three components: a rectangular tower, a round tower, and a broken or zigzag wall connecting them together. The zigzag wall, in turn, consists of two arms and a zigzag section; sections are only rectilinear, and bends are rectangular or acute. Depending on the relief, the zigzag wall has different lengths (the shortest is 7.0 meters, the longest is 25.5 meters, and the zigzag section ranges from 1.5 meters to 9.8 meters) and different directions. Essentially, the Tigranakert fortress follows a triangular model, the mandatory components of which are consecutive rectangular towers (with lengths of the sides ranging from 7.0–8.0 meters), round towers (with a diameter of 9.0 meters), and necessarily a zigzag defensive wall connecting them. The different lengths and directions of the walls represent the technical adaptation of the triangular model to the natural defensive capabilities of the terrain.

The Tigranakert defense system exhibits several distinctive characteristics in its construction technique, including a rock-carved foundation, base implementation with stone blocks, dry laying, reinforcement of the wall strength through block weight, widespread use of swallow-tailed connections, utilization of lime mortar, and construction of the upper part with raw brick. The dimensions of individual components, such as wall thickness and quadrangular tower dimensions, further highlight its architectural complexity. The defense system of Tigranakert bears striking similarities to several classical Near Eastern monuments, including Miletus, Ephesus, Pergamum, Priene, Magnesia on the Meander, Dura-Europos, and some Transcaucasian monuments.

In terms of layout and some architectural solutions, Tigranakert closely resembles Priene with its triangular citadel dominating the terrain, regularly planned quarters at the foot, and zigzag defensive walls. It also shares similarities with Dura Europos, particularly in its defensive wall line (zigzag walls) dating back to the 3rd–2nd centuries BC. However, it bears the most resemblance to Artashat, featuring a triangular citadel dominating the terrain, regularly laid-out quarters at the foot, zigzag defensive walls, and a combination of rectangular and round towers. Certain construction details closely resemble those of the contemporary Armaztsikhe-Bagineti walls. The examination of these architectural parallels confirms that Tigranakert was constructed with the advanced architectural thought and construction techniques of its time. Its preservation status surpasses that of many corresponding monuments, making it a significant benchmark monument from the first century BC to the first century AD.”

The rock-carved foundations of the defensive walls in the Fortified Quarter of the city, their enormous dimensions, the regularity of construction, the perfect symmetry and fine workmanship of the slabs, and the joining of the slabs with the most advanced Hellenistic techniques (such as “swallow tail” connections) undoubtedly testify that they were built with a unified plan by skilled and advanced architects and masters. Such an accumulation of strength, thought, and material and the implementation of a grandiose plan in a specific place were possible only through universal state mobilization. This circumstance further strengthens the belief that we are dealing with a royal and state initiative” (pages 234-335).

Has any Azerbaijani specialist attempted to refute these claims with counter-arguments? No, of course not. Are the Aliyev propagandists familiar with all this? Otherwise, their constant assertion that Armenian archaeologists excavated without permission (when the excavations were carried out with the appropriate permission and procedure of the Artsakh authorities) and their insistence that Tigranakert was invented clearly demonstrate that they are not accustomed to speaking in the language of facts and science.

It is difficult, and often pointless, for a researcher to respond to the nonsensical claims of propagandists.

And why doesn’t any Azerbaijani researcher, who more or less follows academic standards, address these issues?